From ancient myths to modern blockbusters, storytelling has been a fundamental part of human culture for thousands of years. We love to hear stories, whether they’re told around a campfire, read in a book, or watched on a screen. But why do stories captivate us so much? What is it about a good tale that can transport us to another world, evoke strong emotions, and leave a lasting impression?

In this blog post, I’m going to look at the psychological and cultural reasons why humans are drawn to stories and why they continue to be such a powerful force in our lives.

Reading stories with my mum is one of my earliest and most cherished memories and I love writing stories for my daughters (see pic – my debut, in glorious A5 printer paper!)

From an early age, long before we can read, we’re immersed in stories. Initially we’re engaged by the repetition of sounds and patterns which promotes brain development and imagination, develops language and emotions, and strengthens relationships. We have a need for emotional connection and stories allow us to gain a deeper understanding of other people’s experiences, in a memorable and immersive way.

Throughout history, humankind has used stories to share information. Stories can elicit change, warn or teach important concepts, or simply entertain us. We might laugh or cry, feel anxious or angry with the characters we’ve invested in, and any of these provide a powerful emotional connection.

The science bit

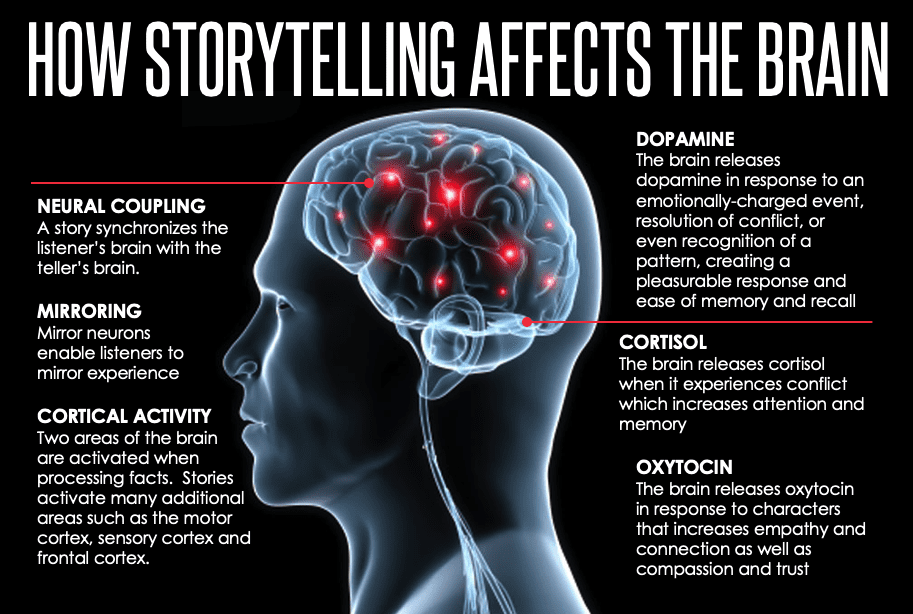

As a storyteller, I find this fascinating, and so is the science bit. ‘Narrative progression’ as it’s called, feeds our brains. Being engrossed in a book or movie stimulates our senses and cause measurable reactions in our brain’s chemistry. Dopamine makes us feel motivated and focused, oxytocin (the ‘love chemical’) promotes feelings of trust and bonding, while endorphins give us a positive buzz.

The two parts of our brain most engaged by stories are the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala. The prefrontal cortex is the area of the brain responsible for cognition and understanding. As we follow a story, it absorbs the information and commits it to short-term memory. The amygdala, however, is responsible for emotion and long-term memory. As our prefrontal cortex receives information, the amygdala essentially “codes” the information based on the emotion we feel, which aids the processing of long-term memories. Both areas of the brain are essential to deep learning and recall.

What makes a good storyteller?

Think about anyone you know who you’d describe as a good storyteller, someone at work or a friend. What makes them so engaging? Chances are they use relatable characters, intriguing plot, emotional connection and a satisfying conclusion, mingled together to create a cocktail of all those chemicals.

As readers, we naturally search for something in characters which we can relate to. It enhances our experience of the narrative and the feeling of trust and empathy can give us a quick dose of oxytocin. The ‘hero’s journey’ from adversity to triumphant success is a familiar trope used by storytellers and forms the backbone of many great stories. The journey from adversity to triumph fires up all the chemicals in our brains and gives us that ‘feel good’ feeling. Subconsciously we search for an emotional connection and without it even a good story might not be committed to memory.

What about happy endings? Again, many great stories lead us to a satisfying conclusion, which gives us another dose of feel good as all loose ends are tied together and the hero or heroine triumphs. If we don’t experience this pay-off, we can be left feeling cheated or disappointed. Think of that series you invested hours in, where the big reveal at the end is more of a limp fob-off. It’s devastating!

Storytelling is critical in our learning process. It aids our engagement with a subject and our retention of information.

Can you use storytelling in business?

Storytelling is just as important in business too, and it doesn’t matter how dry the subject is.

A few years ago I worked as an actor on a commercial project for a battery manufacturer. The client had asked a video production company ABF, to create a training video on battery safety for its employees. ABF presented a concept which went on to win awards and was a wonderfully creative and innovative interpretation of the brief.

They told a story.

The video was shot like a mockumentary and showed a group of employees going through a series of training sessions. They had characters (the employees), plot and conflict (the training sessions) emotional connection (the employee and trainer relationships) and a satisfying conclusion (everyone passed the training, with a hint of romance thrown in).

They created a training tool which people enjoyed and engaged with. It entertained, took people on a journey and helped with their learning.

If you’d like to watch it, it’s on Facebook here.

Humans love stories because they are the framework of our perception. Stories can change our minds, make us feel something new, win our hearts. We react deeply to stories when they communicate information in a primal, insightful way and it’s what we’re looking for when we browse the bookshelves, choosing our next read or when we’re trawling through Netflix.

Some stories have a huge impact on us and can change our perception of society. Here are a few examples of stories that have had a big impact on people’s lives:

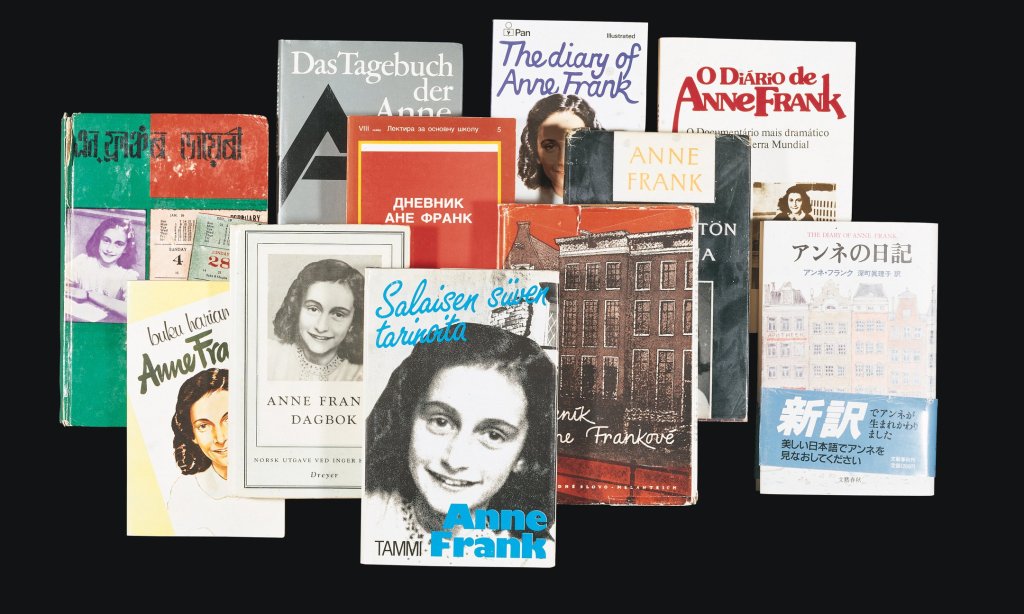

The Diary of Anne Frank: This book, which chronicles the experiences of a young Jewish girl during World War II, has been a powerful tool for teaching empathy and tolerance to generations of readers. Many people credit Anne’s story with helping them better understand the horrors of the Holocaust and the importance of standing up against hatred and discrimination.

To Kill a Mockingbird: Harper Lee’s classic novel, which explores issues of race, justice, and morality in the American South, has been hailed as a powerful tool for promoting empathy and understanding. Many people credit the book with helping them see the world through a different lens, and inspiring them to take action against injustice in their own communities.

The Fault in Our Stars: This novel by John Green, which tells the story of two teenagers with terminal illnesses who fall in love, has been a powerful source of inspiration and comfort for many people dealing with illness or loss. Readers have praised the book for its honest portrayal of the challenges of living with a serious illness, and its message of hope and resilience in the face of adversity.

The West Wing: This TV show, which aired from 1999-2006, has been credited with inspiring a new generation of young people to get involved in politics. The show, which follows the staff of the fictional White House under President Jed Bartlet, has been praised for its smart writing, engaging characters, and optimistic portrayal of the political process.

Personal stories can be incredibly powerful in inspiring people to take action or make a change in their own lives. For instance, hearing the story of someone who overcame addiction or achieved a lifelong dream can be incredibly inspiring, and may motivate others to pursue their own goals and aspirations.

Stories have been a fundamental part of human culture and communication for thousands of years. As human beings, we are naturally drawn to narratives because they help us make sense of the world around us and understand ourselves and others better.

Stories have the power to move us emotionally, inspire us to take action, and connect us with others on a deeper level. Whether it’s a classic novel, a movie, or a personal anecdote, stories can transport us to different times, places, and perspectives, and help us gain new insights and perspectives.

So, the next time you find yourself captivated by a story, remember that you’re not alone – people have been fascinated by storytelling for generations, and it’s one of the things that makes us uniquely human.

Thanks for taking the time to read this post. If you found it informative and entertaining, please consider sharing it with your friends and followers on social media. And if you have any feedback or suggestions for future topics, I’d love to hear from you in the comments below. Don’t forget to subscribe for more content and updates, or pop over to my newsletter page for more crime stuff, direct to your inbox every month.

See you soon.

Wendy